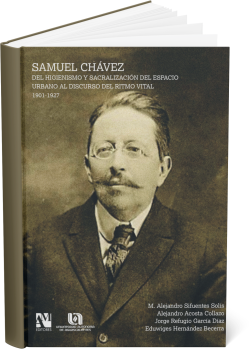

SAMUEL CHÁVEZ: From Hygiene and the Sacralization of Urban Space to the Discourse of Vital Rhythm 1901-1927

Synopsis

The historiographical renewal sparked in the last fifty years, thanks to the unquestionable legacy of the Annales movement in the field of history, has represented substantial changes in the consideration of the types of sources for historical research, particularly in the architectural and urban domains. The histories of territory, places, the environment, and livable space, both architectural and urban and rural, in relation to the body, genders, ideas, theories, family trajectories, construction technology, perceptions, meanings, among others – and no longer solely the authors per se or the physical works and their formal qualities – increasingly demand the diversification of knowledge sources from which historians draw to construct their narratives.

Of course, this movement of renewal does not imply discarding traditional sources, but rather expanding them, complementing them with new types, so that they provide sufficient information to construct a complex object of study. This, complexity, has always been embedded in life systems, both anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic, but only now, with contemporary epistemology – the paradigm of uncertainty and complex systems – have we been able to understand more fully the nature of matter and all the forms of life it fosters. Complexity has always been there, since time immemorial, but the development, resources, and intellectual and epistemological infrastructures had not made it possible to discover and understand it in depth, even though some of the great civilizations of the past, including the Greek and Mesoamerican, had intuited its logic. Thus, with society, culture, and the habitable spaces of bygone eras, it is possible to know, in a deeper way, their framework and functioning, which are complex in themselves, given that we now have more suitable tools to understand, explain, and interpret historical developments, which have always been integrated by networks of relationships and not as mere casual occurrences of isolated events and specific objectives.

In such a context, the creation of a general program idea was a constitutive part of the work of tracking, gathering, and studying various sources and diverse documents that, at the time, within the Academic Body of Urban Architectural Studies of the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes, we suggested naming "Recovery and Development of Sources and Documents for the History of Architecture and Urbanism of Aguascalientes," which included both the facsimile reissue of primary sources and the publication of research derived from their analysis. In this latter option, the present work is framed, which has had the fortunate circumstance of locating a significant part of the personal archive of a relatively little-known architect: Samuel Chávez.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the small but thriving city of Aguascalientes could boast a certain "cultural provincialism" not devoid of cosmopolitan airs: progress—as it was understood then—and the benefits of "civilization" had begun to emerge with the arrival of the first train in 1884 and the start of construction of the General Repair Workshops in 1897, the largest in Latin America at the time; as early as 1824 and until the second third of the century, its relative charm and appeal had attracted the attention of some foreigners, some as visitors, like the Italian traveler J. C. Beltrami, others as permanent or temporary residents, like the French Cornú and Stiker or the German Isidoro Epstein. With the Porfirio Díaz regime, the once-village had to align itself with the general policies for the development of society and the economy of the time, as well as with some of its symbolic-ideological horizons. It is not without reason that Aguascalientes, with city status since 1824 and a population of 34,982 inhabitants in 1900 –thus, among the largest–, was considered one of the most important capitals in the country. Upon reaching that status, it undoubtedly contributed with an urban planning proposal that, in many ways, was pioneering in the country: the Plano de las Colonias, a project by the engineer-architect Samuel Chávez Lavista (Aguascalientes, 1867-1929), behind whose design lay a vision of the city that, on one hand, was circumscribed to the Porfirian symbolic universe, governed by aspects of public hygiene and ornamentation, and, on the other hand, foreshadowed what in subsequent decades would transform into urban social sanitation, pristinely represented by Samuel's second cousin, the architect Carlos Contreras Elizondo (1892-1970). This vision rested on certain notions about the body and its projection in urban space, which this figure maintained and later extended to the fields of the arts of space (architecture), movement or energy (rhythmic gymnastics), and time (music). The following text addresses a fraction of the urban and urban planning history of Aguascalientes in the early 20th century, as well as part of the life and career of this architect, who played a prominent role in both that process and the promotion of artistic education in Mexico.

Downloads

Published

Series

Categories

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.